The arrival of a new executive is an exciting moment containing both opportunity and risk. The new leader has been selected because they bring expertise that the company needs. But the failure rate of new executives hired from the outside is high ‒ between 27% and 46%, according to multiple studies.* On top of that risk, we are now living in an era of unprecedented stress and uncertainty caused by the pandemic, where relationship building at work takes significantly more effort and most informal interactions are impossible.

The good news is that while new-hire integration takes effort, it’s not expensive or difficult, even in the “remote” era. It can also deliver an enormous return on the investment. A 2017 study by search firm Egon Zehnder published in HBR** documented that robust integration of executive hires can shorten time to productivity by about two months, from six months to four.

When I think about the upside of great integration of new talent, I think about Kevin Lobo, who today is the Chairman and CEO of Stryker, number 252 on the Fortune 500. When I first met him, he had just been placed as the Group President of one of Stryker’s business units. Lobo’s integration into Stryker was exemplary. Not only did he get great internal support, but Stryker also hired a colleague and me to facilitate some critical conversations early in his tenure. We captured in writing what his new boss ‒ the CEO ‒ wanted from him when he started, and ensured that he and the CEO were aligned on outcomes for the first quarter and first year in the role. At the three-month mark, we gathered feedback to help him understand how he was coming across to some of his most important peers and stakeholders. Fortunately he didn’t need course-correcting ‒ in fact, we were able to confirm for him that his style and initiatives were well received, so he could accelerate his pace. When the board decided to make a change at the CEO level just 18 months later, Lobo got the top job. His fast start likely made a difference.

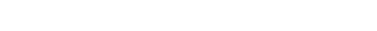

Gleaned from my experience on that project and many others since then, here is a three-month approach that can help accelerate a leader’s integration. While the steps described here are framed for executives, you can scale these steps to apply to just about any new hire situation.

PRIOR TO START DATE

Appoint integration lead. The organization should identify an “Integration Lead” to guide the process, a senior HR professional or internal / external consultant who knows the company well. This person drives the process, facilitates connections and conversations, and gathers insight on how the new leader is doing. (The Integration Lead can also make sure that the leader receives the basics, including information about current strategies and initiatives, insight on the leader’s new team, and relevant systems and tools.)

The hiring manager has ultimate responsibility for the new executive hire success, but they are usually not the ideal person to drive the integration process. An objective third party is able to see the issues quickly, and the relationship between the new leader and their manager is often a critical area where the new hire can benefit from having a sounding board.

FIRST WEEK

Clarify expectations. The Integration Lead initiates and facilitates a conversation with the new leader and their hiring manager, during which they review (in writing) 3-month and 12-month expected outcomes, likely challenges, resource constraints, and cultural factors. This meeting is critical and I budget 90 minutes for it. Getting the expected outcomes down in writing is key to avoid misalignment.

Often there is a disconnect or ambiguity between the new executive’s understanding of why they’ve been hired, and what their new manager expects. Hiring managers sometimes don’t communicate all their expectations plainly, and a new hire hears what they want to hear about expectations during the recruiting process. A clear, honest conversation at the outset is vital, and the Integration Lead ensures that it happens.

First month

FIRST MONTH

Seed relationships. The Integration Lead can ensure that the new leader gets video time with the right people. There’s room to get creative: consider adding informal social time, designed to allow staff at the company to get to know the new leader in a less formal setting.

These days, a new leader’s introductions have to be intentionally cultivated, since there are almost no informal ways to build relationships inside an organization. The Integration Lead can find the right ways to make these conversations happen in a way that makes sense in the company’s culture.

Second month

SECOND MONTH

Evaluate the team. The new leader will need to evaluate their existing team and decide early on whether any changes are needed. If the team doesn’t have the right skills or chemistry, the sooner that gets addressed, the better for all involved.

There’s great value in the new leader acting quickly and decisively to address capability issues with their team. New executives tend to wait too long to make critical talent decisions. (They’re human, after all.) The Integration Lead can be a valuable resource to the new leader in ensuring they have all the relevant data and insight about the team.

THIRD MONTH

Verify progress. In addition to a series of check-ins for the leader with their manager, it’s vital to gather early feedback from peers, stakeholders, and direct reports. Three months is about right; at that point, the leader has been around long enough for their style and priorities to come through, and stakeholders will have a reaction and views. Often leaders are hired to change things, so it’s natural for there to be some pushback from the organization.

The purpose of gathering feedback is to ensure that any tensions or problems surfacing from the new leader’s presence are understood and addressed. At the three-month mark, it’s easy for leaders to make course corrections; but by six months, it may be too hard to recover.

Thoughtful and rigorous integration support for new hires has been a differentiator between organizations that are strategic about their human capital, and organizations that are less strategic, and right now, it’s quite possibly even more important as a means of protecting the substantial investment in the new hire, and limiting the downside risk.

Jonathan Hoyt is a leadership consultant and coach based in the San Francisco Bay Area. He supports boards, investors, and executive teams with executive assessment, coaching, team effectiveness, and executive development experiences.

Sources

* Multiple studies put the 18 month to 2-year executive failure rate in this range, including the following: Brad Smart and Geoff Smart, Topgrading: How to Hire, Coach and Keep A Players, New York, NY: Penguin, 1999; Mark Murphy, “Leadership IQ study: Why new hires fail,” Public Management, 2005, Volume 88, Number 2; Patricia Wheeler, “Executive transitions market study summary report: 2008,” The Institute of Executive Development, 2008; George Bradt, Jayme Check, and Jorge Pedraza, The New Leader’s 100-Day Action Plan: How to Take Charge, Build Your Team, and Get Immediate Results, Hoboken NJ: Wiley, 2006. The percentages cited comes from Executive Transitions Rise, Challenges Continue, IED and Alexcel Research, June 2013 (27 percent), and “High-impact leadership transitions: a transformative approach,” CEB, 2012 (46 percent). [Summarized in “Successfully Transitioning to New Leadership Roles,” McKinsey.com article, https://www.mckinsey.com/business-functions/organization/our-insights/successfully-transitioning-to-new-leadership-roles

** HBR (https://hbr.org/2017/05/onboarding-isnt-enough)